Chat Spam Classifier - Part 1 - Labelling Training Data

The first part of this series talks about how to label a large amount of raw messages as either spam or ham. This labelled data is then used as training data for the classifier which will be described in part two. The third part will deal with how to run the streaming classifier in a production environment. Finally, the fourth part will talk about how to visualize and test the classifier.

- Part 1: Labelling Training Data

- Part 2: The Classifier

- Part 3: Streaming Classification (TODO)

- Part 4: Visualization (TODO)

I recently had the opportunity to solve an issue with spammers for our products. The products are community sites where users can send messages to each other. Many of these messages are from spammers, trying to make others visit websites or to get their emails. The previous solution was to maintain a list of blacklisted keywords. If a message contains one of these keywords, the user would get a warning. Three warnings in a shorter period of time results in a temporary ban. This solution has many drawbacks, since spammers can circumvent e.g. funsite.com with f u n s i t e . c o m. This has caused the list of keywords to grow and grow, year after year. Currently it contains over a thousand of these keywords. Checking against all keywords for every message sent is neither scalable nor accurate. We needed a better solution.

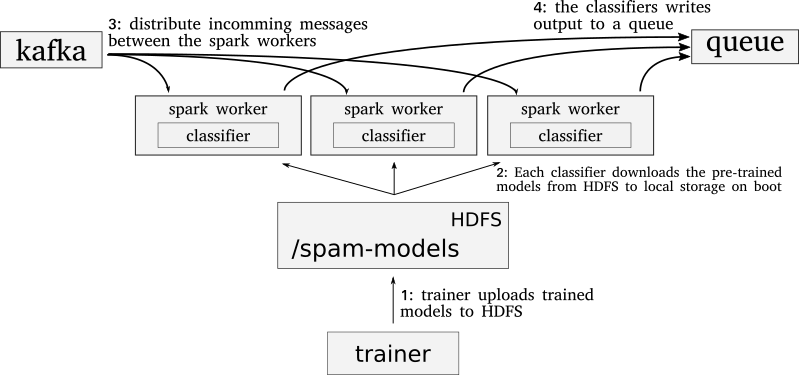

The new solution is an asynchronous streaming classifier using Apache Spark running on Apache Hadoop using Yarn. Incoming messages comes from an Apache Kafka cluster. The models live in HDFS, and each Spark node downloads these at startup. After the models exist on local storage, each worker will load them into memory. The classifier’s publishes predictions in near-real time on a queue for communities to consume. Finally the communities can decide what they want to do with the information given.

Labelling training data

The training data is stored in MySQL so we can improve the data over time through an interface. The table structure I’ll be using looks like the following:

CREATE TABLE `training` (

`id` int(11) NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

`class` int(11) NOT NULL,

`message` text CHARACTER SET utf8 NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (`id`),

FULLTEXT KEY `message` (`message`)

) ENGINE=InnoDB AUTO_INCREMENT=50894 DEFAULT CHARSET=utf8 COLLATE=utf8_bin

The InnoDB engine is because we need the fulltext key on the message column. This way we can match approximate string searches later to find likely spam messages. When your training data has labels you can switch to MyISAM if needed.

In every community we have a way for users to report messages as spam. This way we have a separate dump for reported and unreported messages. Since users might have reported messages as spam that are in fact not spam, this is of course not fool-proof. Since most messages are not spam we don’t want to only dump random messages. If we dump 50k random messages there might be an unproportional amount of non-spam. Instead, we’re dumping roughly 25k reported messages and 25k random messages.

You could of course use more messages for the training data. The only constraint is memory usage and training time. Using around 50k messages gave us a reasonable accuracy of 99.98% after some tweaking. Training on 50k messages and doing cross-validation consumed roughly 30GB of memory for us.

First, we set the class of all messages (included reported) to 0 (non-spam, 1 means spam).

update training set class = 0;

Likely there are some duplicate messages in the training data right now. Duplicates exists both in non-spam and spam. Many users send identical messages such as ‘hi’ and ‘how are you?’. Spammers often send the same message to many users. Having duplicates won’t affect the accuracy of the classifier much, but training time increases:

delete train1 from training train1, training train2

where

train1.id > train2.id and

train1.message = train2.message;

In most spam messages we’ve seen, there are links they want others to follow. Thus we can label all messages with easy-to-find links as spam. In our use case we don’t want users to send links anyway, whether legit or spam. This might not be the same in your case:

update training

set class = 1

where

(message like '%.com %' or

message like '%.net %' or

message like '%.de %') and

message not like '%your-domain.de %' and

message not like '%your-other-domain.com%' and

message not like '%youtube.com%' and

message not like '%facebook.com%' and

class = 0;

Notice the space at the end of your-domain.de . This is because our messages are in German, and sometimes users don’t use a space after a full-stop. Without the space we would find sentences which are not links, since de is a common prefix in German.

Many of our spam messages contains obfuscated links, such as F˔ u˔ n˔ s˔ i˔ t˔ e. c˔ o˔ m and F˖u˖n˖s˖i˖t˖e . n˖e˖t!, to try to circumvent simple keyword matching. Funsite is one domain that often shows up in these ways in our messages. Using regular expressions we can find quite a lot of these messages:

update training set class = 1

where

message regexp 'F.{0,6}U.{0,6}N.{0,6}S.{0,6}I.{0,6}T.{0,6}E'

and class = 0;

Be sure to select before update so you know that the matching messages are actually spam.

After the above we can use the fulltext matching supported by InnoDB to do a fuzzy string search. First add the fulltext index to the table:

ALTER TABLE training ADD FULLTEXT index_name(message);

Then find the most matching messages:

select id, class, message,

match (message) against("Melde dich bitte zuerst hier= Fˈ uˈ nˈ sˈ iˈ tˈ e . nˈ eˈ t!!") as score

from training where

match (message) against("Melde dich bitte zuerst hier= Fˈ uˈ nˈ sˈ iˈ tˈ e . nˈ eˈ t!!") and

class = 0

limit 50;

Change the above string to parts of other spam messages until you can’t find any more non-spam. This can be a tedious process, but it works well to find small variations of the same message.

Next, we have many spam links that ends in two digits. For example funsite18.net and coolplace21.com. These links are usually obfuscated into something like funsite 18++n++e+++t+++ or coolplace 21 ...c,,,0...m.... Using regular expressions we can find these as well:

select count(*) from training

where

message regexp '[0-9]{2}.{0,5}[nN].{0,3}[neNE3].{0,3}[tT]';

select count(*) from training

where

message regexp '[0-9]{2}.{0,5}[cC].{0,3}[oO0].{0,3}[mM]';

Now we can run the classifier using this training data print all false positives. False positives means messages labelled as ham but classified as spam. Since we likely missed some spam messages, we want to find the false positives and update their label to ham. If you have most of your data labelled correct, the classifier will find what you’ve missed. For example during the evaluation phase:

# y_true is the labels from the training set, y_hat is what the

# classifier predicted (% probability of being spam)

for index, (yy_true, yy_hat) in enumerate(zip(y_true, y_hat)):

# if the classifier is unsure likely it's not our spam messages

if y_true == 0 and y_guess >= 0.5:

# printing the messages from a copy of the input matrix since

# the one used for training contains the transformed messages

# which are not human-readable

print('[guess: %s, true: %s]' % (yy_hat, yy_true))

print(X_valid_original[index].encode('utf-8').strip())

Update the training data based on what the classifier finds. Split the data at random to get both training data and validation data. You have to run the classifier a couple of times this way to find the miss-labelled data in the different folds. An easy way is to let some library do cross-validation for you a power-of-ten times, for example scikit-learn. If you validate on the completed set you might not find all messages.